As I announced in my last post, the next few contributions of this blog will dig deeper into each of the nine capabilities which I see as essential for succeeding in business ecosystems. Let’s start with a particularly tricky one – the one I call decentration competence.

A couple of years ago we conducted a global survey among more than 150 companies to better understand the challenges they face with their engagement in business ecosystems. It turned out that ego-focused mindsets and restricted cognitive maps ranked highest in the list of perceived barriers: 72% reported a lack of understanding of network dynamics, 69% a mindset of introversion/self-centricity, and an equal 69% an inability to think beyond traditional ways to do business. The percentages were even higher among firms with more than 10,000 employees – stunning, but not surprising.

Why is our Ego-System so Strong?

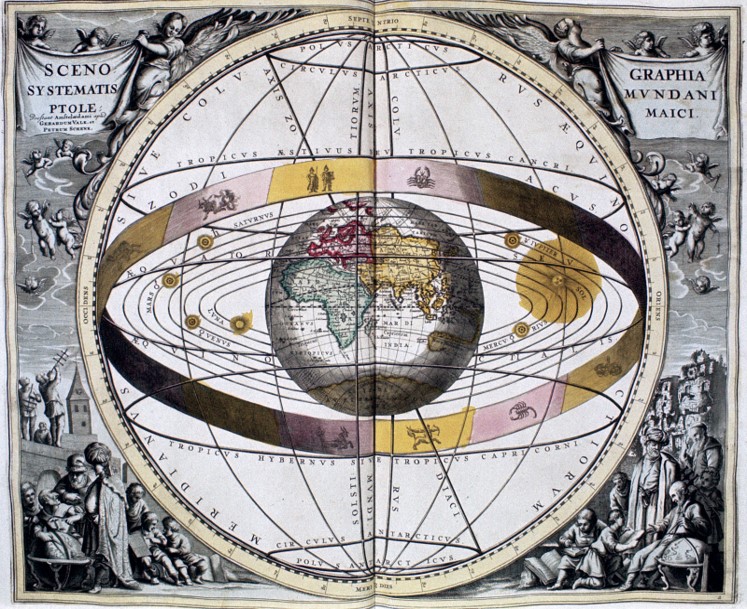

Ecosystem thinking does not come easy. We quite likely face an evolutionary hurdle in taking ourselves out of the center and seeing us as interconnected part of a larger system; after all, mankind needed centuries to move from a geocentric world view over a heliocentric one to today’s view of the universe, finally realizing our peripheral position within the cosmos.

Seeing ourselves as the center of the universe seems to be deeply engraved in the human condition, something that became exacerbated over centuries by what sociologists call “occidental rationalism” – a specific Western way of thinking which largely dominates today’s world. Cornerstones of this thinking include a deep belief in the supremacy of one’s ideology or religion (may it be Capitalism, Communism, Christianity, or Islam), which is held as the only true truth that must be spread unilaterally across the globe, if necessary with the sword. It also includes an anthropocentric relationship to our natural environment that puts humans apart from and above their biosphere (the biblical “subjugate the earth”), and – especially in the United States – an emphasis of individualism as an organizing principle of business and society.

This world view does not go well with dialectic thinking, a mindset that prioritizes “and” over “either-or”, where contradictions are a productive source, diversity is cherished as enlarging opportunities and perspectives, and community is viewed as important as individual success. It also has a hard time with systemic thinking that emphasizes horizontal interconnectedness, interdependence, and the collaborative construction of reality over mechanistic control.

I know – the above is pretty fundamental and relates to our overall societal and ecological development. I still think it is important to think about the larger context when we talk about business ecosystem leadership. The tendency to put our ego-system before the eco-system – which comes with a limited ability to see ourselves as part of a web of connectivity that we continuously co-constitute – is one of the most important barriers that we need to overcome if we want to succeed in the new ball game.

The Ego-System of Organizations

Now, more specificly, let’s talk about organizations as socio-technical entities. Here I see three main additional factors that further reinforce our tendency to egocentrism:

Shareholder value above everything

The principle of maximizing shareholder value as the first and foremost purpose of the firm is maybe one of the biggest factors that fosters corporate selfishness. The infamous Friedman doctrine – still the bible for Wall Street – makes economic value added the guiding star for strategy and organization. The primacy of short-term profit comes with an externalization of social and ecological costs. While many may shrug about the damage this way to do business does to the overall social and ecological system, we must not forget that it also does significant collateral damage to ecosystem partners. In its ultimate form, maximizing shareholder value is about extracting customers, squeezing suppliers and employees, destroying competitors, manipulating regulators – all within legal constraints, of course – or sometimes not. It is easy to see the inherent egotistical nature of this narrow economic model – a model that is supported by reward systems that further shape the mindsets of leaders, especially the CEO and the board. The incompatibility with the necessities of ecosystem engagement is obvious.

Inward orientation fostered by the complexity of large organizations

Size and complexity is another factor that fosters organizational egocentricity. The larger a company gets, the busier it becomes with its internal affairs as the need for coordination of operations and the negotiation of perspectives grows. Multiple hierarchical levels and horizontal differentiation mean that decision processes must consider more stakeholders; they take more time and become less transparent. At the same time, the intensity of micropolitics and internal power plays grows exponentially. Projects dedicated to internal (re)organization and change initiatives proliferate, more and more executive time is tied up in internal meetings. I vividly remember the case of a Fortune 100 company where 90% of the calendar of senior executives was occupied with internal meetings only. The obsession with self-occupation made them insensitive to changing market dynamics, to the point that they were unable to seize growth opportunities beyond the narrow horizon of their traditional routines.

Established industry leadership

Finally, industry leaders in late stages of business model cycles who once shaped the rules of the industry have a particularly hard time overcoming an egocentric attitude of dominance; after all, their way of doing business made them stars. Blinded by their historic success, they continue to define their industry within traditional boundaries. They may see the sign of disruptive change on the horizon, but their perfectly tuned operational engine and a deeply embedded mindset of what it takes to be successful makes it almost impossible to move. They have a narrow perception of their strategic arena which goes hand in hand with an increasingly outdated understanding of competition. In a nutshell, they suffer from the “disease of the leader,” a dangerous combination of arrogance and inability to abandon mindsets whose shelf-life is nearing its end. We all are familiar with the graveyard of previous shooting stars such as Kodak, Blockbuster, Polaroid, or Sears, and we read daily about the struggles of many giants of the “old economy.”

From an Ego-System to an Eco-System Orientation.

If you consider the above – our human condition, deeply engraved societal sensemaking patterns, an economic theory that fosters egotism, bureaucratization that leads to inward orientation, and the pathologies known as the “disease of the leader” – letting go of the ego-system seems like an almost insurmountable task.

But we know that the success of ecosystem engagement – and the performance of the ecosystem itself – depend on transcending ego-systems. We know that ecosystem-based value creation requires a new type of strategic thinking, led by a thorough understanding of a company’s role within the relationship network that informs its actions. This is only possible if you can take an elevated, superordinate view of the overall systems’ strategy, operations, performance, and profitability. I call this ability to step out of your ego-centered frame of reference and see the world “from above” decentration competence. Through such a decentered perspective all roles within the ecosystem’s stakeholder universe become more understandable, and aspects of your own role become a matter of open negotiation.

Given all the constraints that foster ego-system thinking, it is not easy to develop decentration competence. However, there are three principles which, if you pursue them consistently, will open up rigid mindsets and enlarge your cognitive maps towards the new paradigm:

1 Know – really know – your own purpose, within the system and beyond

It may sound counterintuitive to put the understanding of your own purpose and identity as the first condition for letting go of your ego, but without a solid basic strategic orientation (BSO) and core values that are shared across your organization you will lack the anchor that allows you to act with confidence in an open, fluid environment. Elements of the BSO include a decision about which industry/business you are in, the time horizon of your engagement, your qualitative and quantitative goals, the role you want/can play towards your most important stakeholders and, last but not least, the meaning of profit within the overall goals of your company. Working on your BSO is a continuous work in progress, an adaptive process that gets informed through your outside experiences and the fluidity of your business context. In essence, it’s a learning process towards an ever-better γνῶθι σεαυτόν – knowing thyself.

2 Know – really know – the key stakeholders that constitute the system.

Such stakeholders are foremost customers (they create the purpose for the existence of the ecosystem in the first place) and all other key members of the partner universe that are essential for the value creation of the system. Each significant partner in the ecosystem has their own purpose, their own BSO, their own identity – just like outlined above. Each member also comes with their strengths, weaknesses, cultural peculiarities, internal power dynamics, and more. The deeper you can appreciate what drives the “others’’, what role in the ecosystem they want to and are able to play, how they strategize, how they organize, etc, the better you will be able to step into their shoes, take on their perspective, and interact/collaborate appropriately. There are many ways to develop this “understanding of the alien” – cross-boundary dialogues in the spirit of mutually appreciative inquiry, the ongoing pursuit of traditional marketplace intelligence, structuring the collaboration with partners as joint learning experience, sharing insights about each other, and more. Done well, the journey towards a mutual understanding will develop the all-important trust that is indispensable for creating a high-performing ecosystem.

3 Know the system

Finally, decentration requires not only knowing yourself and the others. These are just preconditions for a holistic view of the entire ecosystem. To elevate your perspective to a truly decentered level, you must be able to understand (1) the relationship between yourself and each partner of the system and (2) the interplay between all external stakeholders, including yourself. It’s like a game of multi-dimensional chess, in which each move influences the moves of all others. Being anchored in a strong own purpose and knowing – really knowing – the others is critical here: The better you know yourself and the idiosyncrasies of your partners, the more you can understand ecosystem dynamics. And the better you appreciate these dynamics, the better you can shape the unavoidable political power game. The path towards “knowing the system” is an active and reflective engagement that creates experiences and contexts. Create spaces where you can make sense of these experiences, ideally together with your critical stakeholders. Actually, creating and shaping such spaces is one of the most effective ways to achieve business ecosystem leadership.

To summarize the above: decentration competence is a complex capability that first and foremost requires a strong organizational identity, based on a clear basic strategic orientation, an unbiased awareness of your own capabilities, and an understanding of the culture that drives your organizational behavior. To sense and understand the driving forces of your ecosystem partners, you must be equally able to assess their strategy, capabilities, and culture. Finally, you must appreciate the relationship not only between yourself and your partners, but also the dynamic interplay of the overall system

As such, decentration competence is a Janus-faced affair. Internal and external awareness are two sides of one coin that depend on each other and must be managed coherently. Only organizations that are anchored in a clear purpose and that trust their capabilities can credibly define and sustain their position within the ecosystem and resist the natural inclination to retain control. They can control by letting go.